In 1978, we arrived in Iqaluit. At that time is was called Frobisher Bay. Talk about culture shock!

When I think of it now and what it must have been like for my mom who was only in her late 20’s, I can’t imagine what it must have been like. The courage it took her to create a new life and a new story for her family. One that I will forever be indescribably grateful because of who it made me be.

We learned so much about this new place we found ourselves in. We were in the tundra, above the tree line and in the land of the midnight sun. My parents were both very community minded and we were involved in as much and as many community events as we could manage.

This is where my passion for an Indigenous way of life began. In school, our classes included sewing and soapstone carving and making traditional Inuktitut arts and foods.

People know that the bay of Fundy in NFLD has the highest tides in the world – the figures I find say it can be up to 16m/ The tides in Iqaluit are pretty close. Between 8 & 11m are the figures I could find.

Since Iqaluit is located on a bay and the conditions are right, every day, the sea drains out of the bay and leaves the ships sitting on the ground where trucks and equipment then drive out to them.

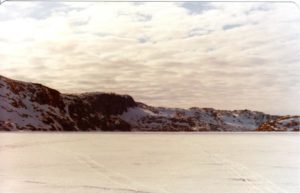

Our favourite times were going out on the land. The bay when the tide was out and playing in the tidal pools and exploring the bottom of the seabed was definitely a favourite pass time.

The days get pretty long in the arctic and my mom, being very resourceful, quickly found ways to fill the days when winter came and it was too cold to go outside. One of my favourite memories and what I see now as the foundation of my love and respect for the Earth is picking lichen to dye the wool.

My mom got Muskox wool from from someone (I wish she was here so I could fill these gaps in) and we spent hours and days brushing the wool to prepare it for the spinning wheel. Then, our favourite part – heading out to the tundra to harvest lichen for dyes. The #1 rule was that we could only take one small piece of lichen off of a rock and that had to find another rock to take another small piece. The reminder that we were on the tundra and that each piece of lichen takes 100’s of years to grow was ever present.

I have always struggled living in the south with the callous attitude of the general population towards the sanctity and preciousness of all living things – especially in the forest. The lush, green, forest that I treat with such reverence. I try and be kind in my attitude towards the ignorance that I see. I try and remember that my childhood was worlds apart from most people’s and that it was such a gift to my brother and I to have been raised in such extraordinary circumstances. That my love of and connection to nature comes from having spent the formative years of my life in small, Indigenous communities where learning to respect the land is essential to survival in a much more visceral way than it could ever be to people raised in southern cities where it’s so easy to take things for granted and to never have to think about all the conditions that need to align for food to be brought to your table. For clothes to end up in your closet.

Another great blessing is the realization that community is of the utmost importance. That not only are we dependant on the natural world for our survival, but that we are also dependant on the people in our community.

There was a dramatic blizzard, no one could leave their houses for days and when the snow stopped blowing and we could see anything out the window, we found the true meaning of the words “snowed in”! Although getting out was not impossible, it would have had to have been out the second story window of our house. My predominant memory os the storm was my mother crying at the kindness of the “strangers” that shovelled a path through the snow to our door so we could come outside.

My class photo grade three

One of the hardest things to get used to was the daylight. By the end of June, It was light almost 24 hours a day. We had to have heavy garbage bags on our windows to sleep, and there were always kids and people outside even in the middle of the night. My dad took this picture of me outside at 1:00am. I think the only reason we were out there is because we were catching our plane to go south in the morning

After a couple of years in Iqaluit, my parents decided that they’d like to experience living in a hamlet. So, Kimmirut – Lake Harbour at the time – was our next destination

Not far from Iqaluit, it is a much more isolated community that is only accessible by twin-otter airplane. It is located on an inlet and the hamlet is named for a large outcrop in the inlet shaped like a heel Kimmirut is the inuktitut word for heel. It is served by a small airport and the majority of supplies come in once a year by sea lift. A ship comes to the mouth of the inlet and barges make their way to the community where everyone gathers to watch the supplies for the year.

We had a very large store room in our house and my parents had to guesstimate what to order for dry goods for the year.

The population of Kimmirut was about 400 people at the time and is absolutely my favourite place that we have ever lived. The community was very close and tight knit. Because of our experiences living in the arctic, I have a living memory of another way of life and it is the reason that I have any hope for humanity

Another thing that I only realized later in life is how living on the ocean was also fundamental in the formation of my core values. When you live in harmony with the land, that’s exactly what you do. You don’t try and harness and control mother nature, you adapt to and live in harmony with her. Living in the south now for so long is something that I continually struggle with.

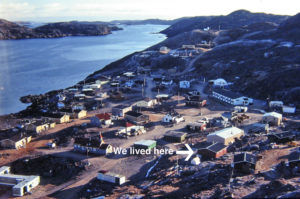

Here is a photo from the air of the whole community.

Winter in the north is incredible – it’s when you can all of a sudden reach places that have been inaccessible while the ice was gone. Hunting is so much easier and my dad was quickly accepted by and joined the local hunters to get meat. Just because one person actually shot the caribou didn’t mean that’s whose caribou it was. Elders are always taken care of first and then meat is distributed afterwards.

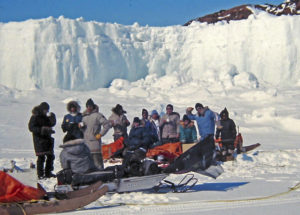

Caribou and seal were plentiful when we were there, I’m sure that things are not the same now. Here’s my dad with some local hunters getting ready to go out on the ice

And with a seal.

I realize now that because my dad was who he was, our experience of the north is also unique because he worked hard to become accepted in the community. My dad studied Inuktitut and not only did my brother and I learn it in school, he also encouraged us to practice it with him at home. Because he was so respectful of the Indigenous people , their culture, their language and their way of life, our family had the special honour of truly becoming part of the community.

The sea played such an enormous role in everyone’s life and one of the most celebrated times was when the bay froze enough to be able to make it out to the “floe edge”. This is where the action really happened! It made the arctic sea accessible and this is when the hunting got good – whales, seals, polar bears. All now within reach.

Some more pictures from Kimmirut

The Hudson’s Bay “store” -really more of a trading post

Some of Kimmirut’s famous carvers. Kimmirut’s claim to fame is it’s unique green soapstone.

Inukshuks have become almost cultish-ly popular in the south in the last couple of decades. It’s definitely something appropriated from the Innu people whose very lives depended on these structures to navigate the tundra. There are very few landmarks on the tundra and hunter’s lives are dependant upon them.

My birthday party

Can’t forget one of the most breathtaking things about the arctic – the northern lights. With an almost boundless horizon and some of the biggest skies you’ve ever seen, almost total darkness for a lot of the year, The northern lights are almost always there to haunt you!

Another of my favourite memories is the picture just below. With the HUGE tides and the water from the sea constantly coming in and out of the inlet, a wall of ice forms along the rocks on the inlet. The ice also moves up and down on that wall throughout the day. My dad got my mom, my brother and I to stand in front of it on the pack ice – another consequence of the large tides – the ice is made up of huge heaves and depressions from the movement of the tides in and out of the inlet and being on the pack ice required constant vigilance and caution. So, there we were, posing for the picture when the ice heaved and my mom had a huge moment of panic. Teasing my mom was one of my dad’s favourite pass times and this photo has always been a family favourite

Another way this experience has had such a profound effect on my life is that during the winter solstice, the whole town gathered in the community centre for weeks of traditional food, games, singing and dancing. Gifts were given to every child in the community and even though we didn’t live in total darkness during the winter as we weren’t above the arctic circle, it was pretty close and being together during the darkest and longest days of the year helped ensure that everyone was kept busy.

And then there were the endless snowbanks – ripe for jumping into and for soft landings.

Living on Baffin Island as a child forever changed who I am. It gave me a lifelong respect and admiration for Indigenous culture and ways of life.

The realization took a long while to manifest in me, but I am now aware that this experience I had has had a profound influence in the person I am today.

Someone who is dedicated to intersectionality and anti-opression principles

Someone who sees and understands that our very existence is dependant on us adapting to nature and not the other way around.

Someone who has dedicated their life to fighting for a fair and just world. A life that embraces and respects Indigenous culture as the foundation upon which we should be living our lives. A life dedicated to returning us to our roots. To a way of life that takes care of the many not the few. A life where material possessions are appreciated but not worshiped.

Off we go now to the western arctic because why not?